AI Does Not Fit the Shape of Schooling

Schooling has a shape. That shape is multidimensional with various concavities formed slowly over time, like grooves in a canyon, to accommodate the many purposes we have imposed on schooling—cognitive development, social development, mental health, physical fitness, workforce training, nutrition, economic mobility, and so on and so on.

Tyack and Cuban called this shape a “grammar” and used it to explain the aspects of schooling that seem very resistant to change. I am calling it a “shape” because it allows me to post this image.

The Education Department issued a report this month on artificial intelligence and its implications for teaching and learning. Among its recommendations:

Work toward AI models that fit the fullness of visions for learning—and avoid limiting learning to what AI can currently model well.

I watch teachers enact the fullness of learning within the shape of schooling. I watch them do it, even within this misshapen angular thing.

For example, I watch Liz Clark-Garvey in Brooklyn, NYC, tell students, “I’m gonna flash an image. You’re gonna miss it. Think about what might be mathematically important.” She flashes a picture of a set of tiles in front of the class and because no one had enough time digest it mathematically or formally, she receives contributions from all around the class, of all sorts, which she helps develop into more learning for the class.

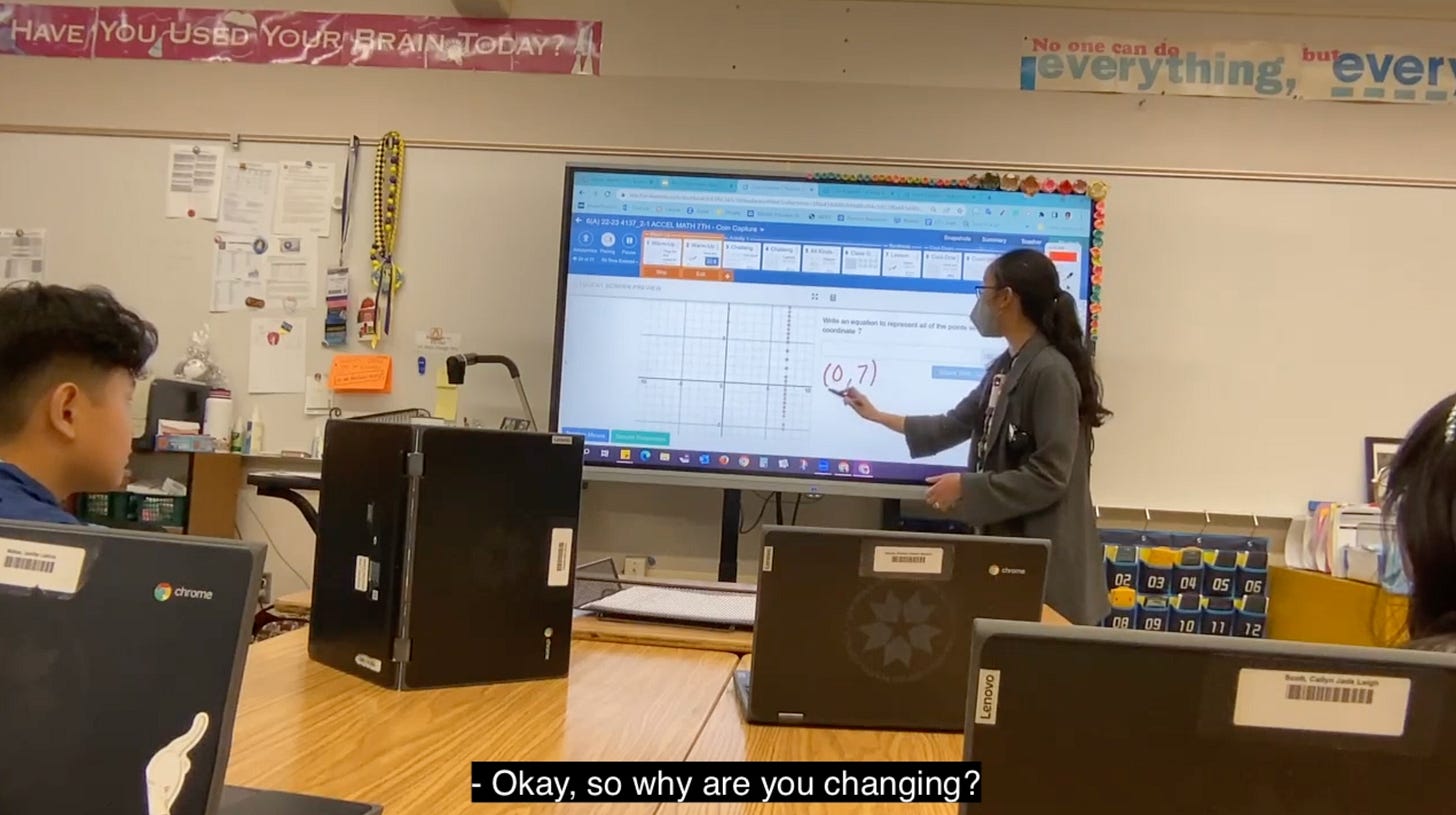

I watch Gen Esmende in San Diego, CA. She shows students the points that they have created on a graph that have an x value of 7. She asks the class to name points that match that relationship. A student says (0,7). SHE WRITES THAT WRONG ANSWER DOWN I STRESS AGAIN SHE WRITES THAT WRONG ANSWER DOWN. Her voice betrays nothing. Her hand betrays nothing. She knows the class will sort this one out and the class does and learns a great deal about math but an even greater deal about who holds mathematical truth in the world.

Both of those moments—excellent, transcendent—fit within the shape of schooling. The classes are both age-graded. A bell will announce the arrival and departure of students. The class learns math that is aligned to standards.

In both of those classes, you’ll also find curricular materials that make room for student thought. You’ll find teachers who are genuinely and lovingly curious about their students’ thoughts. And, consequently, you’ll find students who are eager to see and be seen by one another as being smart.

Let’s hypothesize an AI agent that is omniscient. It never hallucinates. It is invisible and accessible to every student at all times. I just don’t know at what point in either of those classes a student would want to consult it. Most students would rather participate (even silently) in a moment of social learning with their classmates or teacher even though they aren’t anywhere as smart or quick as this AI agent we’re hypothesizing.

I can readily see possibilities for AI in teacher support, teacher professional development, and I’ll even concede its potential in situations where a teacher isn’t available. I can see how AI might fit around the shape of a school. But in the classroom, during teacher-led whole-class instruction, in the middle of this shape we have constructed as the primary vehicle for student learning, I cannot see where an AI agent fits. It has the wrong shape.

What Else?

As another example, rizzGPT does not fit the shape of the way humans date. Like many proposed applications of AI in schooling, it could be transformative except that it misunderstands its context in a fundamental way. (I know this thing is probably a joke but it is a useful joke to me.)

The US Office of Education report on AI is really great. Here are a few of my favorite excerpts.

The first decade of adaptivity in edtech drew upon many important principles, for example, around how to sequence learning experiences and how to give students feedback. And yet the underlying conception was often deficit-based. The system focused on what was wrong with the student and chose pre-existing learning resources that might fix that weakness. Going forward, we must harness AI’s ability to sense and build upon learner strengths. Likewise, the past decade of approaches was individualistic, and yet we know that humans are fundamentally social and that learning is powerfully social.

[..]

Listening session attendees noted that the rhetoric around adaptivity has often been deficit-based; technology tries to pinpoint what a student is lacking and then provides instruction to fill that specific gap. Teachers also orient to students' strengths; they find competencies or “assets” a student has and use those to build up the students’ knowledge. AI models cannot be fully equitable while failing to recognize or build upon each student’s sources of competency. AI models that are more asset-oriented would be an advance.

[..]

We envision a technology-enhanced future more like an electric bike and less like robot vacuums. On an electric bike, the human is fully aware and fully in control, but their burden is less, and their effort is multiplied by a complementary technological enhancement. Robot vacuums do their job, freeing the human from involvement or oversight.

"SHE WRITES THAT WRONG ANSWER DOWN I STRESS AGAIN SHE WRITES THAT WRONG ANSWER DOWN. Her voice betrays nothing. Her hand betrays nothing. She knows the class will sort this one out and the class does and learns a great deal about math but an even greater deal about who holds mathematical truth in the world." This is freaking inspiring. Trying to do this myself initially felt wrong, and yet I'm getting better at it and it's starting to feel GOOD because what you say is true, and I'm realizing it is good teaching (through PD, through reading this substack and other articles). Thank you for sharing your observations of Gen Esmende and others' excellent teaching ongoingly. It's helping me be a better teacher.

I love the concept of the shape of school. For so long we have been trying to fit children who are not squares, circles or triangles into a school system that is a very particular shape. We have asked children to change instead of asking the school to change.