[FULL TALK] Math Without Mistakes

As the school year kicks off here in North America, I’m releasing a video of a talk I gave through much of the last school year. I hope it will nourish some of your conversations at the start of this new year about math, teaching, and students.

Abstract

Throughout the talk, I wonder about the negative self-conceptions kids develop in math class, and why they seem so intense relative to other school subjects.

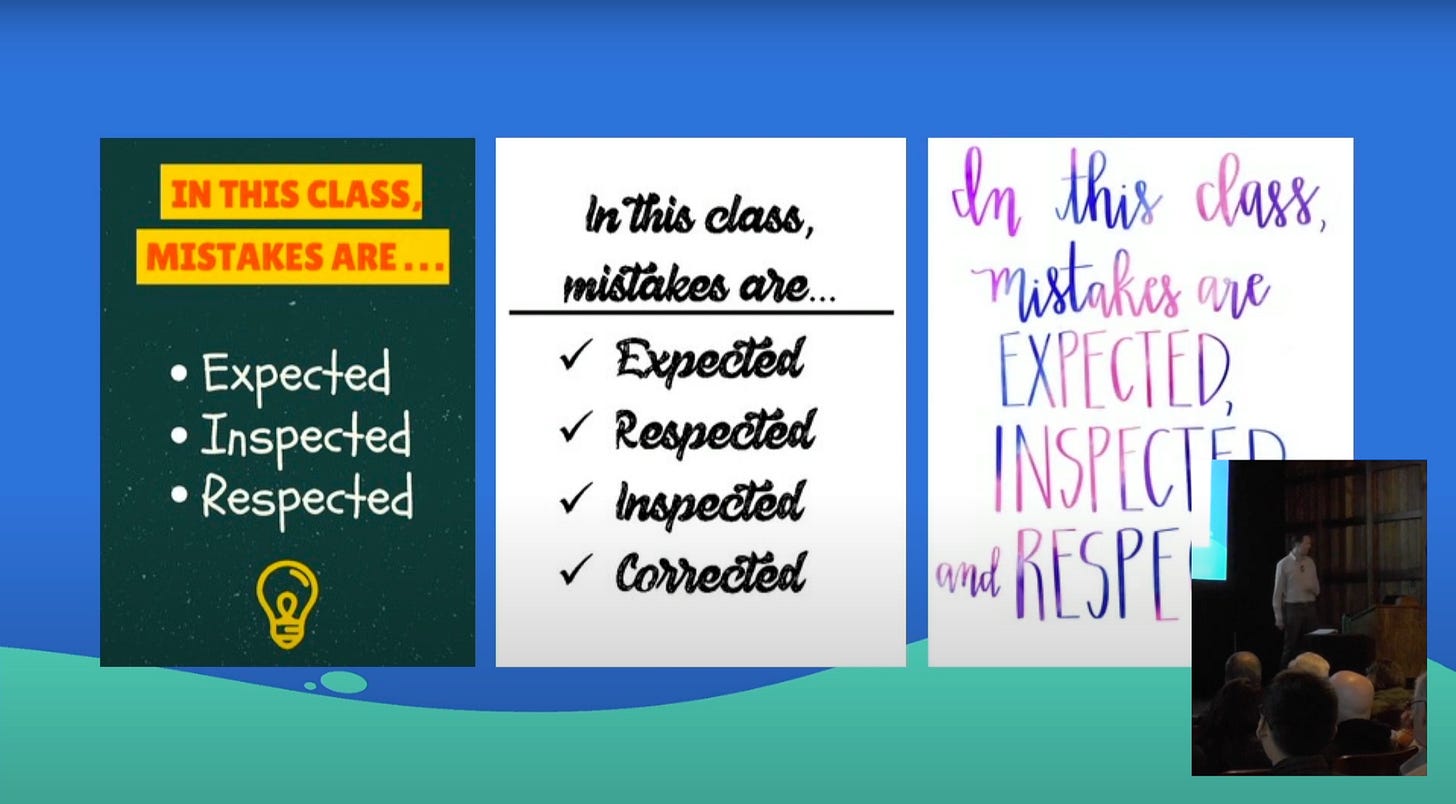

I describe my appreciation for the ways the math education community has united around the idea that incorrect answers need not be sources of shame.

But I encourage math educators to go still farther and identify wrong answers as valuable, rather than just not shameful. Basically, I think that the growth mindset movement has helped math educators calibrate their compasses in a very useful way and I’d like us to walk farther along its heading.

What transforms a student’s relationship to math, other people, and themselves is not to be told that incorrectness is a temporary state en route to something more valuable (a/k/a being right) but that there is value in the wrong answers themselves. My claim is that other disciplines emphasize that latter message more often than math.

“This was a mistake but that’s okay” vs. “This answer is wrong and also very interesting.”

“You’re wrong now but can be right someday” vs. “You’re wrong now and are also making a very valuable contribution to our learning now.”

Along the way, I tried to offer teachers a) a personal experience of being wrong and smart at the same time b) some of my favorite quotes about students and their thinking, c) some concrete teaching moves and curriculum choices to create classrooms where students feel like their thinking is valued whether it is correct or not.

Behind the Scenes

Here is a totally gratuitous note about the “talking to a large room of people by yourself” genre of human communication. I have received opportunities to communicate in that form for the better part of my career and in many ways, my craft has not improved. I don’t feel like my slides are any better designed now than they were a decade ago, for example. Ten years later and I still feel like I speak too fast and slouch too much.

One way my craft has changed—and I think improved—is my ability to facilitate a kind of emotional, interpersonal connection in a room full of strangers. I’m not sure it can be felt in a YouTube recording. I experience it pretty rarely in webinars. But under certain circumstances, all of us in a room together form a kind of improbable connection, a form of intimacy where all of us are spontaneously and collectively open to new possibilities for ourselves and our work. Me most of all maybe. I know it’s happening because the hairs on my arm go nuts and a lump rises in my throat in a talk I have given so many times I could recite it under a strong sedative.

I’m trying to figure out why that does and doesn’t happen in talks. As best as I can tell, that kind of openness to an emotional experience starts with the presenter. Is the presenter willing to experience new possibilities for their work live, in real time? I think it’s also very hard to access anyone’s emotions directly. If I’d like for all of us to reconsider why we’re doing what we’re doing, what we hope teaching can be, what we value about students and ourselves, it needs to start with experiences that are more concrete and less emotionally fraught. If I had to plan a new talk right now, I’d try to include three of the major food groups of our work: curriculum, pedagogy, and beliefs. And I’d try to serve them up in that order, using what we teach and how we teach as a pretext to discover and discuss why we teach.

What Else?

I’m just not fluent enough in the language of philanthropy to parse the significance of the layoffs at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and their divestment from Summit Learning. I only want to note this paragraph:

Eight years ago, the ways whole child development showed up in classrooms were largely divergent — that is, they either focused on child development or focused on learning. But brain science shows that the two are interrelated. To that end, we have partnered with researchers and educators to build better interventions, and then validate and scale them.

With generative AI, the personalized learning era is either coming to a close or taking on a new form. Either way, the interrelation between social and cognitive learning feels like something venture and philanthropic capital is going to have to learn and re-learn for the rest of time.

(FWIW as long as we’re here I think CZI’s Along platform is a really nice move in the direction of strengthening teacher-student connections. It’s 100% agnostic of content, though. The real challenge IMO is using social connections to strengthen cognitive connections and vice versa.)

¶

The HMH Educator Confidence Report is a survey of teacher attitudes towards their profession and includes a bunch of interesting questions about artificial intelligence. Help me metabolize this slide. What do you make of it?

¶

I think teacher-as-non-playable-character is a description of student learning conditions that may prove pretty durable over the next few years.

Hi Dan! Thank you for sharing your talk. Was super interested in it.

One thought to share: I also find wrong answers to be very valuable because they can be equally telling about misconceptions around teaching—maybe a poorly designed lesson, sequence of lessons, or actual question. And even if I think my lesson was on point, it can still link back to feedback, practice strategy, or the fact that the actual question being asked just sucked or wasn't worded properly.

So many factors can contribute to the formation of a mistake, but I think a lot of the time we operate on the default assumption that considers them only from the point of view of poorly formed student conceptions.

I NEVER tell a student their answer is wrong. Instead I ask EVERY student who gives an answer to tell how they were thinking to get the solution they got. As children go through the thought process to explain their thinking, if they have made an error they often are able to correct their own mistake. This mistake then is described as a method that didn't work. If they don't see a problem then other students in the class may see where the thinking doesn't work and chime in with a question (always a question) that would help lead the student to seeing the mistake ie student: 5+5 is ten right? Then is 6+5 twelve? How much did you add to 5+5 to get 6+5? and so on ( I work with little kids K-3). Sometimes the child might be encouraged to build to show and that often shows the mistake. No wrong answers only mistakes in thinking or counting etc. I cannot tell you what a different mindset this makes in my little students and it enables them to stick with it until things make sense because they know they will.