ChatGPT as a generative AI platform turned one year old last week. During that short period, it has amassed hundreds of millions of users, increased its valuation by billions of dollars, generated enough palace intrigue for its own prestige cable drama, and provoked more newsletter posts from me than I would have predicted a year ago.

However, ChatGPT as a set of technological aspirations for education celebrated a much older birthday last week, turning somewhere between sixty and one hundred years old depending on when you start the clock.

Look at these predictions about technology in education, all of which I have sourced from Audrey Watters’s authoritative Teaching Machines.

Stanford University professor Patrick Suppes in 1966:

One can predict in a few more years millions of schoolchildren will have access to what Philip Macedon’s son Alexander enjoyed as a royal prerogative: the personal services of a tutor as well-informed and responsive as Aristotle.

Science journalist George A.W. Boehm in 1960:

Programmed teaching, if it lives up to its early promise, could in the next decade or two revolutionize education. It may also have an important impact on such U.S. educational problems as the shortage of teachers and the construction of schools.

Engineer and inventor Simon Ramo in 1957:

Ultimately, with the proper cooperation between experts in education, expert teachers, experts in trigonometry, and experts in engineering these automatic systems, we can evolve that high level of match between the human teacher and the machine that we seek in that improved high school.

These predictions are very hard to distinguish from predictions about generative AI in 2023.

Sal Khan:

But I think we're at the cusp of using AI for probably the biggest positive transformation that education has ever seen. And the way we're going to do that is by giving every student on the planet an artificially intelligent but amazing personal tutor.

Anne Trumbore:

And today, the abilities of ChatGPT to write essays, answer philosophical questions and solve computer coding problems may finally achieve Suppes’ goal of truly personalized tutoring via computer.

McKinsey & Company:

Our current research suggests that 20 to 40 percent of current teacher hours are spent on activities that could be automated using existing technology. That translates into approximately 13 hours per week that teachers could redirect toward activities that lead to higher student outcomes and higher teacher satisfaction.

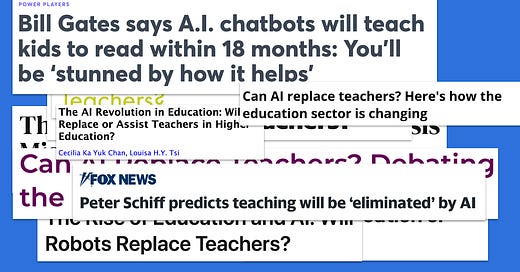

In each century—this one and the last—futurists have predicted that new technologies will receive widespread usage in schools, ensure equitable access to education, allocate teacher labor more effectively, and transform student outcomes. Futurists of the last century were incorrect in their predictions and the cards are not looking great for the futurists of this century.

What were you expecting?

I am trying to celebrate ChatGPT’s birthday here, not write its obituary. But if you look at the predictions of leading technologists and futurists, generative AI is clearly not on track to meet even their most modest expectations for student or teacher use.

What have we seen so far? There was Natasha Singer’s profile of Newark Public Schools’ use of Khanmigo earlier this year. There was a profile last month of a $40,000 / year private school in Texas. Sal Khan’s private Lab School too, of course. Shouldn’t we have seen more this year?

Additionally, edtech firms like Magic School and Khan Academy only seem to report aggregate usage—the total number of students or teachers who have ever clicked “Sign Up” or used a tool once. At this point, shouldn’t we see reports of active usage, a growing number of students and teachers who return to use these tools week after week and day after day?

Shouldn’t we see a growing number of students, teachers, and caregivers talking about the indispensability of generative AI in education?

Shouldn’t we see a growing number of school systems hanging a significant portion of their student learning needs on generative AI?

Shouldn’t we see a growing number of teachers talking about how generative AI has restored so much more of their energy at this point in the year? Or how their relationship to their work or students has changed in some fundamental way?

Shouldn’t we see the kind of deliberate and sustained uptake of generative AI in education that we saw with photocopiers, graphing calculators, digital projectors, interactive whiteboards, personal computers, and the internet itself?

Perhaps we are too early for this kind of accounting. Perhaps we just need to wait a little longer. Perhaps teachers just need a little more professional development. Perhaps the technologies just need to improve a little more, become a little cheaper, a little faster, a little more accurate.

You can tell yourself any story you want. Perhaps right now we are mere weeks away from an inflection point in generative AI usage among students and teachers.

Or—perhaps this technology is the wrong shape. Perhaps generative AI is a square peg for schooling’s triangular hole.

Schooling has a connection challenge, not a content challenge.

Futurists have made this same bet on technology for 100 years only to see the dice come up snake eyes every time. That’s because futurists misunderstand the challenge of education as a content challenge, a challenge of generating and delivering the right content to the right students.

But education is a connection challenge. Education is, first, the challenge of connecting students to the project of schooling, investing them in its goals and processes while recognizing that many students have found those goals alienating and the processes dehumanizing. The challenge of education is to connect students to their own capacity for brilliant thought, to help them realize that their minds are capable of more than they themselves may believe possible. To connect students, one to another, helping each one recognize the value in the other. The challenge of education is to connect a student’s existing ideas to new ones, and for the new ideas to meet the student much more than halfway.

Computers and the internet are connective by their nature and therefore offer lots of transformative possibilities for education. But we will only see the kind of transformation imagined by our leading futurists if they’re able to control for a host of personal student characteristics, abstracting away the student’s need for human connection and “reducing the concept of animals and human beings in order to make them machine-operable,” in the words of social critic Paul Goodman in 1964.

2024 Plans

What are your plans for 2024? Me, I’m spending a few days in December working on a small experimental generative AI project trying to help teachers give more effective feedback to their students. This is a square peg for a square hole, though, a text generation tool for people trying to generate text. I also have a few speaking engagements on generative AI coming up, mostly to investor, foundation, and edtech types. (For example at the ASU+GSV Airshow.)

But I don’t know how much more helpful I can be here, honestly. If you are unpersuaded by the last century of education technology that a) students have needs that cannot be met by technology, and that b) those needs cannot be abstracted easily from the needs that technology can meet, I’m not sure what another newsletter from me will do.

Also, selfishly, I’m not sure how much more I want to help here. A large part of me is very happy that so many edtech players have scurried off the field to play with this new fidget spinner. The playing field feels clearer than it has in years.

So in 2024, I plan to keep an eye on generative AI, especially to see if it transforms into some unexpected new shape, one that more closely fits the work of schooling. But I plan to double my focus on the playing field as I understand it, working directly with students more often, studying more classroom video, working with teachers on a new professional learning program, and thinking much more about the ways teachers and their tools grow together.

Generative AI has been pretty good for increasing my readership and for helping me crank out content to meet my 2023 goal of one newsletter per week. But I’m most grateful for the ways generative AI has helped me better understand teaching and learning, how it’s helped me better understand the difference between what it offers students and what students need, the difference between generative content and generative connection. So I’m wishing ChatGPT a happy 60th birthday today but the party is for teachers.

2023 Dec 11. A Brief History of AI in Education

I began my teaching career in 1968! Yikes! In the last 25 years I have seen a myriad of teaching tools and systems come and go. In the Us we are constantly looking for the easy way to do something and in terms of teaching there is no easy way. Most of my years teaching involved the lower grades K-5. Teachers at this level need to know how to teach mathematics. They need help in the classroom from a person who can both teach them and teach them how to teach their students. AI cannot do this. We need to put our energy and money into supplying trained PEOPLE at the elementary level to work side by side with teachers demonstrating, showing , supporting, and talking with them as they watch and see what happens as their children become engaged learners. This takes time. Lesson planning is time intensive and requires the planner to have intimate knowledge of each pupil in their class. This cannot be turned over to technology. As a math specialist who spent 95% of my time in classrooms working alongside teachers I KNOW this way produces the results we are looking for. My teachers became teachers who loved teaching math and their students became active and productive math learners.

I have read quite a few takes on the one-year anniversary of ChatGPT and even written one myself. This is the best one by far!