> import humans

Talking with our engineering team about education technology.

A bunch of Amplify software developers are gathered at our Brooklyn headquarters and they invited me to talk with them about teaching and learning. Here is what I said.

It’s an honor to chat with you all for a couple of reasons—

One, because the work accomplishments that make me the most proud have all come through collaboration with software engineers, and

Two, because I have a reflexive assumption you all know my ATM pin number and I would like to stay in your favor.

New Answers to an Old Question

I also think it’s really important that we chat right now because whenever technology advances, we need new answers to a very old question.

The same question applies to society more broadly, of course. As technology advances, what value do we offer each other—assuming it’s for something more than using our body moisture to cool data centers or turning our organs into soylent to feed our overlords.

Back to education, though. Everyone at every edtech company should have an opinion on the question:

What good is a computer and a teacher to a learner?

The technologies that we use for learning were not invented for that purpose. They were not invented by people who understand or necessarily care about learning. Education always gets the technological table scraps from better capitalized industries. If we are not opinionated here, we will inherit the opinions of those other industries.

Another reason to have a strong opinion here: the more heterodox our opinions within edtech, the more our success depends on all of us pulling in the same direction.

The Dominant Paradigm in Edtech, and Our Own

It’s easy to think that everyone in edtech is pulling in the same direction—everyone kinda liking kids and teachers and cafeteria workers in roughly the same way—but that isn’t the case. Let me invite you to experience two versions of the same mathematics—one from the dominant edtech paradigms and one from our own. I'd like us to wonder what these different experiences say about the value of a computer to a math class.

Try a wrong answer—one that’s random and one that’s sensible. Do you know the most common wrong answer kids offer when trying to plot the point (6,0). Right—so try the point (0,6) and then try something a little more random.

Notice how in the dominant paradigm you receive the same feedback with both points—an evaluation that you’re right or wrong. Meanwhile, we plug kid thinking into an outlet that carries more voltage. We connect their ideas to mathematics by way of this thieving little crab, which shows them their point whether its right or wrong.

What happens when you’re eventually correct? In the dominant paradigm, you flit across the surface of the mathematics, answering several similar questions until you’re evaluated to have mastered that mathematics. Meanwhile, we seek to move deeper below the surface of student thinking, asking students to think about new locations in unfamiliar quadrants.

Say whatever you want about the dominant paradigm in math edtech, but you can’t say it hasn’t been tried. You can’t say it’s new. One hundred years ago, Sidney Pressey gave kids questions and asked them to select from five multiple choice responses at which point a dial would turn to the next question if they got the answer right. Evaluation then and evaluation now.

Neither can you say it has lived up to its promises. Many of the most popular tools have found positive efficacy results only after throwing out 95% of participating students from their sample. A national study of schools engaged in this edtech model found insignificant gains in reading and math gains that were significant but hardly transformative.

This is mystifying to many.

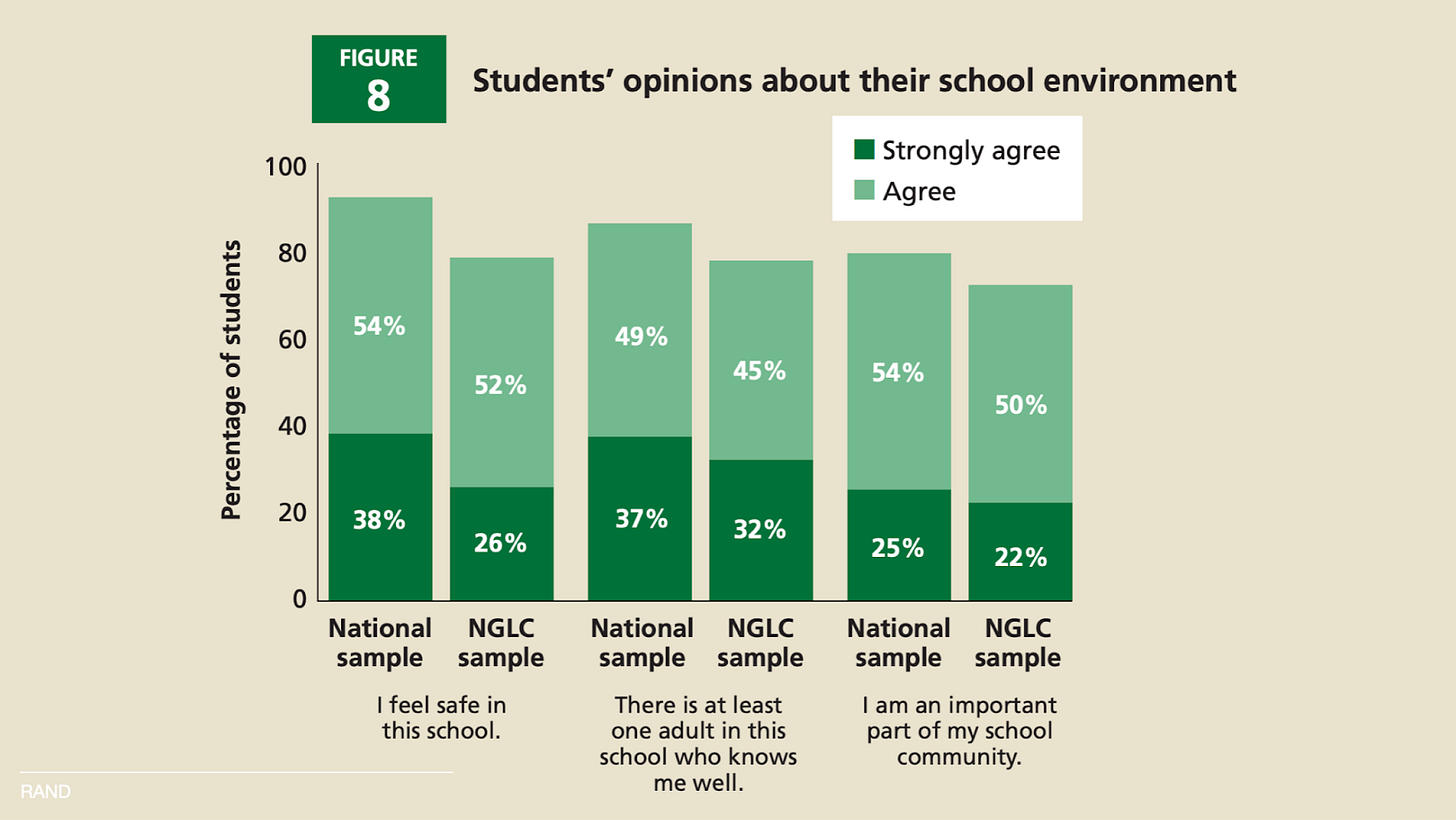

This is mystifying to many until you recall that teachers are the largest in-school factor supporting student learning and that learning increases when teachers and students have a positive working relationship. The same study that found middling achievement gains for the dominant edtech paradigm also found students who felt diminished feelings of safety, belonging, and relationship.

When you watch teachers working within the dominant edtech paradigm, you see their relationship with students transformed from nurturing to supervisory. What more can those teachers do but patrol the rows of desks, making sure kids are staying on the right tab and staying off of Retro Bowl.

import humans

Believe me—I understand why so many companies operating in the dominant edtech paradigm prefer not to import humans to the extent we do. Importing humans—teachers and students—into our technology model means importing their different strengths, their many frailties, their contradictory aspirations, and their non-deterministic nature.

Humans do not compile like software. Software compiles the same way every time. Compiling humans is like spinning a roulette wheel. They compile differently on Friday than on Monday, in March than in December, after they’ve had their coffee than before. But humans have been learning and enjoying learning with humans for much longer than the dominant edtech paradigm has been wishing humans and their differences away.

This is the question before us and I would like to share with you a new idea for how these digital tools can become teacher partners instead of teacher proof. It is an idea that still overwhelms me with excitement even after I have spent months picking it apart on various drawing boards. Here it is.

And that is why I am glad we had this talk. Because bringing this vision to life will require all of us to have deep expertise in our own field and an appreciation for the expertise of one another. It will require us to understand and avoid the failed ideas of the dominant education technology paradigm. Creating a tool that is a new and unprecedented teacher partner will require us to partner with one another in new and unprecedented ways. I’m looking forward to it.

I love that the guy who invented a push-button learning machine was named "Presser."

I love the perspective you share in your weekly posts. This one especially...

"As technology advances, what value do we offer each other".

These are the questions that should keep us going. Yesterday, I had the pleasure of listening to a podcast from a fellow Substack author, Varun Godbole-a former Google employee that is really taking some time to think about similar things to you. He suggested in the podcast "there's a lot of similarity between the various processes for the proactive cultivation of wisdom and the proactive cultivation of curiosity, open-mindedness, exploration, overall adaptability" as he advocated for a "tech perspective" moving technology closer to an agent that makes humans more wise, thus enabling human flourishing at scale. I can only cross my fingers and hope that there are many more humans such as yourself and Varun and we just don't know about all of you yet but the work of you and others will transform the space into a wiser world! Every educator and human needs to work towards systems that advocate for exploration and curiosity-especially in math.........with first line "import humans".