Earlier this year, Laurence Holt synthesized several glowing efficacy studies from several edtech companies and noted that their glow emanates from roughly 5% of the students in the studies. The companies excluded roughly 95% of students from their studies for not meeting arbitrary thresholds for usage.

Like Holt, I am sympathetic here. These companies would like to study the effect of usage rather than non-usage. But does anyone think those 95% of students are randomly distributed among the population of students? Of course not.

It is likely that these are the kids who most need help.

It is also likely that roughly 5% of students will use whatever product they’re told to use at whatever level they’re told to use it and will likely benefit from very nearly any resource. They are checked in, rather than checked out. They are already climbing the ladder towards academic success and material security. Adults have told them, implicitly and explicitly, “This ladder is for you.” And any time they take even a small step upwards, another rung materializes to meet them.

Meanwhile, many of the other 95% of students are checked out. Rather, they have been checked out. They have been told, implicitly and explicitly, that this ladder is for others, for people who don’t look like you, for people whose families have more money than yours, for people who think about school and math in ways that you don’t.

Various edtech developers and operators have told us recently, “We see these kids and we have a plan.”

For example, Philip Cutler, CEO of edtech tutoring company Paper, has noticed his product supports one group of students better than another:

It became increasingly clear that while we excelled in supporting self-motivated learners, a critical gap remained in addressing the needs of students requiring more structured support.

Andy Matuschak is an applied researcher and software developer who recently described his reasons for leaving the world of K-16 edtech:

I have done a bunch of collaborations these past few years with professors in higher ed teaching large classes and what I experience again and again is just an enormous fraction of the student body that is just fundamentally not engaged with the class. And I don't think any amount of UI chicanery or AI involvement is going to change that and I think I basically don't want to put myself into that problem solving situation. In some sense, that's actually why I left Khan Academy.

Sal Khan was recently asked about these students by CBS Mornings anchor Tony Dokoupil. His response:

I think people who don’t want to engage will find shortcuts that existed even before this and people who want to engage more are going to be able to do that. But I think the role of the classroom is super important, the role of the teacher and the parents, because they can make sure that the students are engaging in the right way.

One plan here is to say, “Okay, the challenge of educating the 95% is not a challenge I want to work on.” I actually have a lot of respect for this position, especially given some of the alternatives.

Another plan is to say, “Our product will need to change.” This has the benefit of being both true and within your locus of control.

Another response that is present above and prevalent within edtech is to blame the kids, to say that the students who are not engaged by your product are not engaged because they “don’t want to engage.” This perspective maintains it is not the responsibility of the edtech developer to understand why 95% of students seem to have checked out of their product. Happily, for those developers, this perspective can account for any product shortcoming. If you see students disengaging en masse from an experience that, for example, treats them and their classmates like broken widgets traveling along individualized conveyor belts, well, we can say that they are simply getting out what they are putting in. This perspective also maintains it’s the teacher’s responsibility to remedy the liabilities of the product. The teacher here should function like a line worker, flipping widgets back onto their belt whenever the belt throws them off.

“Our product does not fail to meet the needs of students,” says much of edtech. “Students, teachers, and caregivers fail to meet the needs of our product.”

Teachers and edtech need a different partnership.

Many products imagine teaching as the negative space around their product. “Teaching is that which our product does not do or do well.” This perspective wastes teachers. It has a strong sense of self but little understanding of the people who determine much more of a kid’s educational outcomes.

When adults describe the formative moments in their math education, the moments they decided math education was or wasn’t for them, they rarely describe an interaction they had with software. They more often describe interactions with people. A teacher who convinced them with one casual, cutting remark that math wasn’t for them. Or a teacher who convinced them they were brilliant beyond even their own reckoning.

If you want to help the 95%, you need to help teachers. You need to help people. People check kids out of their education so people will need to check kids back in.

In our partnership with teachers, for example, we ask questions that students can get right and wrong in different, interesting ways. Then we make that thinking visible to teachers.

How are you helping Jalah and Sam?

For huge majorities of edtech developers, the ones who have never taught the 95%, the ones who have perhaps spent most of their own life surrounded by the 5%, this all might seem a little abstract.

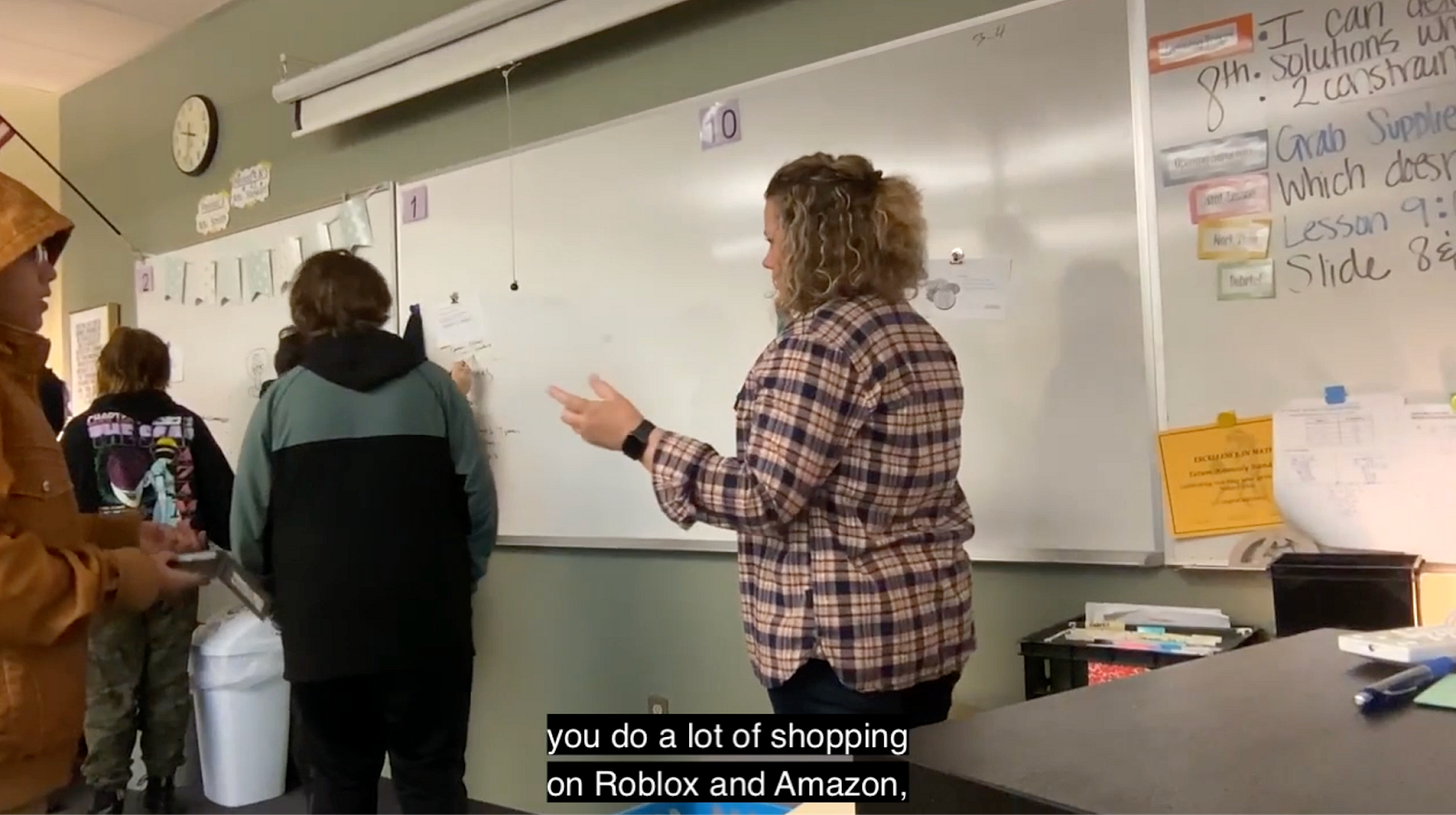

I encourage those developers to watch middle school math teacher Jalah Bryant teach a student named Sam who seems pretty checked out. (At one point, he flips a middle finger to the camera.) I encourage them to watch Bryant perform persistent work to check Sam back in. How does your product support Jalah in that work?

In our case, we support Bryant with a question that has different right answers, some of which are very accessible to a novice.

Watch how Jalah works to convince Sam over and over again, sometimes using our curriculum and other times using her knowledge of his personal interests, that he knows a lot of useful stuff here!

Once she helps Sam remember what he knows, Jalah works quickly to get him credit for that knowledge with the rest of his group.

She applies persistent pressure throughout the clip. “Do one [more combination] and then I’m gonna walk away.”

This is the work that 95% of students need. They need it at different levels and at different times, but you can’t discount this work if you want to support their learning. You can’t blame them for needing this work.

There is nothing dishonest about saying, “We only really understand the needs of the 5%. That’s who we’re working to support. We can help the world’s elite become extra elite.” But if you intend to support the 95%, you have to ask yourself, “How is our work working with teachers like Jalah and for students like Sam?”

That clip is the real deal. Best video of real teaching I've seen in a long time, maybe ever.

Bravo! Thank you for highlighting the very real work of math educators who must continually nudge their students into their own brilliance. This work is not recognized or valued nearly enough.