In the first year of the COVID pandemic, two states waived many of their typical requirements for teachers, allowing anyone with a bachelor’s degree to teach. After reviewing end-of-course exam results, supervisor evaluations, and other data, researchers concluded that the students of this group of emergency-hired teachers did not differ significantly from students taught by traditionally licensed teachers.

The researchers suggest this group of emergency-hired teachers is likely unique, disproportionately comprising paraprofessionals and aides who already had jobs within schools, relationships with staff, relationships with students, and who were ready to work when their schools moved to virtual teaching. As an addition caveat, end-of-course exam scores dropped significantly for all students after states began administering them again, so I’m curious what role floor effects are playing here. (i.e. I suspect Usain Bolt and I would not differ quite as much in our 100 meter time if we were both encased in concrete from the neck down.)

I chatted with an AI engineer yesterday who was contemplating a move into K-12 education. I raise this study just to point out—especially to newcomers—that education is very often a confusing space, one with a self-contradicting set of mandates, one where important outcomes are often difficult to measure or where measuring them generally requires timelines long enough to weaken the controls enjoyed by other disciplines like medicine.

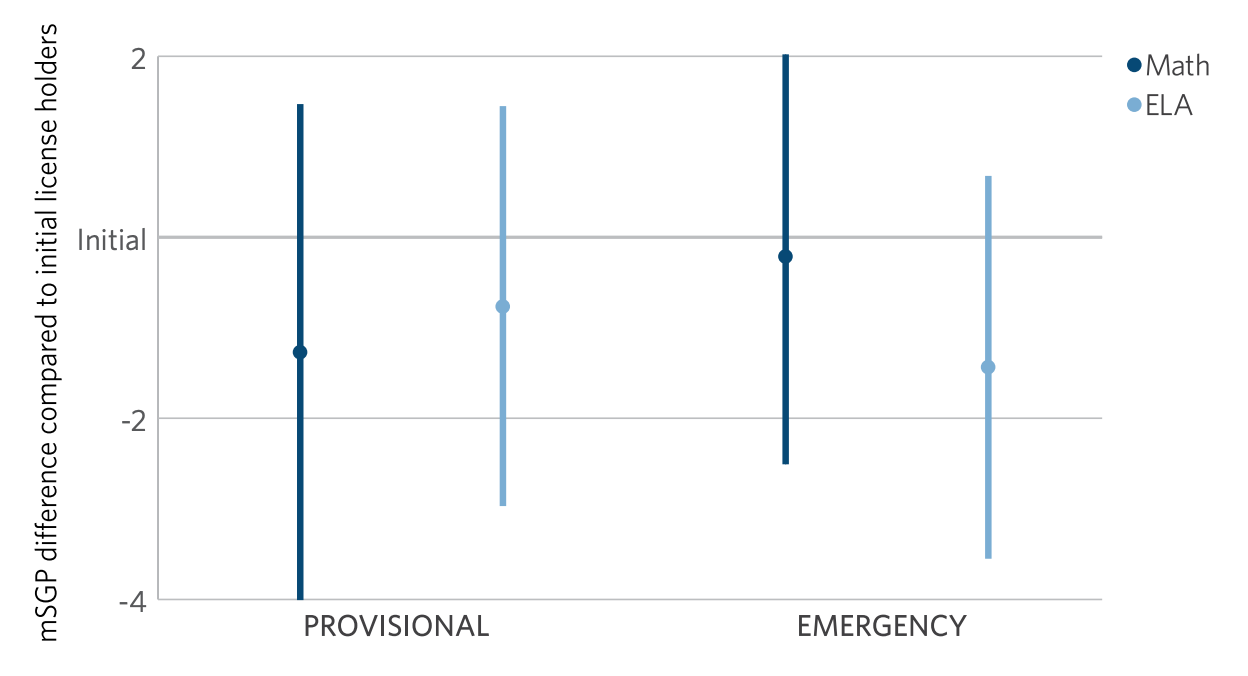

For example, we know that teachers are the in-school factor that is most influential on student learning but researchers struggle to attribute much of the variance between teachers to any of the categories you might expect—SAT scores, undergraduate GPA, coursework taken, degrees awarded, certification route, number of years of experience (past year five anyway), etc. (See this review.)

A Cheat Code for Education

I am convinced that a huge amount of the enthusiasm for AI in education (and for teaching machines historically) is simply the wish for a cheat code, a wish to press ↑↑↓↓←→←→BA, enter god mode, and escape our current condition where it’s hard to understand how to select, train, and support the people most essential to the education of our children.

I’m suggesting that if you’re serious about this work, you can’t cheat code your way around teachers. If your work doesn’t account for teachers—the way they work, the way they move through a class, the tools they use, the way they think about their students, their aspirations for their work, the outcomes for which they’re accountable, the vastness of their experiences prior to teaching—you will make a meaningful impact on student learning only by accident.

One possibility is that great teachers are born but that good teachers can be made. Even if we can’t select for teacher quality through categories like “certification route,” there is a growing body of evidence for different experiences that support teacher development. For my part, I am especially happy to work on the tools teachers use every day—software and curriculum in my case—because just as we use our tools, our tools are also using us, and making us. There is a career’s worth of satisfying work here, with abundant possible progress, but there isn’t a cheat code.

I've always thought that improving as a teacher is a lot like improving as a writer, a continuous process of trial and error, learning from error, coming up with a purposeful approach to improvement and trying again. The most important trait I've observed in myself and others around progressing in one's teaching, more than smarts, knowledge of teaching techniques, or anything else is embracing that mindset of learning from "failure" where failure means falling short of some meaningful and (reasonably lofty) goals one sets for oneself. To me, all those metrics you list that don't seem to tell us much simply don't relate to the actual work of teaching.

I wonder if we need more paths to the teaching profession. I was struck by…

The teachers working under these licenses also helped diversify the state’s classrooms, as they were about twice as likely as other beginning educators to be Black, Hispanic or Asian.

The path through the state towards a credential can be an expensive one. Is the EdTPA costing us some diversity? Should there be a less expensive and arduous path that would allow local districts to develop and certify a teacher? Would this lead to a staff of more home grown teachers with more investment in the community? Would that help?